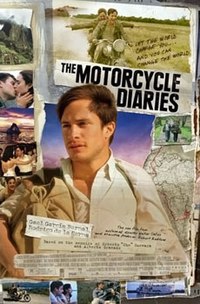

I saw two films on TV over Christmas that touched me deeply, in different ways. The first was The Motorcycle Diaries by Walter Salles, based on the journals kept by Che Guevara and his friend Alberto Granado during a life-changing epic motorcycle ride round South America. It's a directorial tour de force, drawing on genres for what they can offer, discarding them when they no longer serve the purpose. It's not a buddy movie, however much the film examines the changing relationship between the two friends, their affections, their differences - both emotional and political. It's not a road movie, despite the essentially picaresque narrative structure: this happens, that happens, they move on, they meet new people, they fall in love and out of it. What makes it more than a collection of episodes is the cumulative effect the episodes have on the two main characters, particularly Ernesto, a sensitive asthmatic who can't tell a lie for the life of him, or anyone else. The clearest signs of the ruthlessness that enabled him to become the Che of legend are when he simply can't not tell the truth, however painful to others, and to himself, it might be; it's a feature of revolutionaries that the individual sensibility can be sacrificed for the larger notion, and it's to the credit of the wonderful Gael Garcia Bernal that he makes this seem an entirely admirable characteristic.

I saw two films on TV over Christmas that touched me deeply, in different ways. The first was The Motorcycle Diaries by Walter Salles, based on the journals kept by Che Guevara and his friend Alberto Granado during a life-changing epic motorcycle ride round South America. It's a directorial tour de force, drawing on genres for what they can offer, discarding them when they no longer serve the purpose. It's not a buddy movie, however much the film examines the changing relationship between the two friends, their affections, their differences - both emotional and political. It's not a road movie, despite the essentially picaresque narrative structure: this happens, that happens, they move on, they meet new people, they fall in love and out of it. What makes it more than a collection of episodes is the cumulative effect the episodes have on the two main characters, particularly Ernesto, a sensitive asthmatic who can't tell a lie for the life of him, or anyone else. The clearest signs of the ruthlessness that enabled him to become the Che of legend are when he simply can't not tell the truth, however painful to others, and to himself, it might be; it's a feature of revolutionaries that the individual sensibility can be sacrificed for the larger notion, and it's to the credit of the wonderful Gael Garcia Bernal that he makes this seem an entirely admirable characteristic.Quite by chance, I saw Papillon a few weeks ago, for the first time in over thirty years, and it's interesting to compare how the two films dealt with leprosy. In Papillon, the lepers are not only people with a problem, but also - if not primarily - a testing ground for the hero's courage. For this to work, the head leper is suitably monstrous. In The Motorcycle Diaries, on the other hand, the lepers are seen as an opportunity for compassion, and solidarity. (Interestingly, both films see nuns as hypocrites). What the film left me with was a sense that one life can change many lives and that the quality - and consequence - of those changes might be utterly unpredictable, but that maybe we shouldn't be put off by this. Maybe there is a case for the kind of struggle Che continues to represent. Perhaps the real hero, though, was Che's friend, who set up the Santiago Medical School (I think), creating the one thing for which Cuba can wholeheartedly and unreservedly be praised, and that might never have existed without the work of Che and Castro.

The other film was The History Boys, based on the Alan Bennett play, with the extraordinary Richard Griffiths as Mr Hector, the 'general studies' teacher, preparing a group of sixth-formers for Oxbridge entrance in the early 1980s. Hector's a charismatic teacher but of a curiously low-key sort, as far removed from the character portrayed by Robin Williams in The Dead Poet's Society as is humanly possible.It's always interesting to me to see how much most genuine teachers loathe DPS and how much it's adored by students (in Italy, at least). It's as though teachers recognise how easily the kind of power Williams portrays can be misused and understand that it is, essentially, no different from that of his less hip colleagues. He's still just telling people how to behave. Which, of course, is exactly what students want: to be told what to do by someone who seems to be providing some kind of cool alternative, both to the other teachers and to what the world has to offer. What makes Hector such a wonderful creation is the extreme modesty of his tyranny (he is not, after all, a facilitator). To all intents and purposes, he lets his boys get on with it, as they improvise scenes in a French brothel or act out the final scene from Brief Encounter. They're fond of him, more than they realise, but not enchanted, which is as it should be; enchantment is the last thing a teacher should be up to.

The other film was The History Boys, based on the Alan Bennett play, with the extraordinary Richard Griffiths as Mr Hector, the 'general studies' teacher, preparing a group of sixth-formers for Oxbridge entrance in the early 1980s. Hector's a charismatic teacher but of a curiously low-key sort, as far removed from the character portrayed by Robin Williams in The Dead Poet's Society as is humanly possible.It's always interesting to me to see how much most genuine teachers loathe DPS and how much it's adored by students (in Italy, at least). It's as though teachers recognise how easily the kind of power Williams portrays can be misused and understand that it is, essentially, no different from that of his less hip colleagues. He's still just telling people how to behave. Which, of course, is exactly what students want: to be told what to do by someone who seems to be providing some kind of cool alternative, both to the other teachers and to what the world has to offer. What makes Hector such a wonderful creation is the extreme modesty of his tyranny (he is not, after all, a facilitator). To all intents and purposes, he lets his boys get on with it, as they improvise scenes in a French brothel or act out the final scene from Brief Encounter. They're fond of him, more than they realise, but not enchanted, which is as it should be; enchantment is the last thing a teacher should be up to.The other theme of the film, of course, is what we do with being gay. Hector is gay, as is Irwin, the new-broom-sweeping-clean teacher and one or two, maybe three of the boys, which made me wonder, with some regret, why my own school days should have been so resolutely straight. I found Hector's plight as a frustrated ephebophile touching and couldn't rebuke him for the delicacy of his solution to it - gauchely groping his pillion rider as the lollipop lady halted the traffic (the motorcycle connection?). But I also wondered why Posner, his star pupil, whose attitude to his own gayness seemed stoically matter-or-fact rather than self-reproaching, should have wanted to take the same rather Edwardian path of sexual self-sacrifice that his teacher/mentor had. The film often seemed to be lurching between two quite incompatible worlds: one of caution and evasion, in which EM Forster - and possibly the young Alan Bennett - might have felt at home; and an altogether more contemporary one in which sixth-formers swore in front of their betters, offered themselves up for oral sex and saw learning in terms of its providing access to Thatcher-era success.

The best part for me, despite all the sexual, and sexy, undertow of the film, was towards the end, when Hector explains how much he hates those people who say they 'love words' and 'literature' (you have to hear his lugubrious enunciation of these terms to get the full contempt), as though genuflecting to high culture were a way of not having to think about its implications.

No comments:

Post a Comment