I’ve just finished Warwick Collins’ new novel, The Sonnets, which draws its inspiration from Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence and the circumstances in which it was written. It’s a brave man who decides to narrate an episode from Shakespeare’s life in the first person - who opts, in other words, to impersonate the man himself - and an even braver one who pens a couple of extra sonnets at crucial moments in the narrative, but Collins pulls off the first with considerable elegance and skill, and the second by the skin of his teeth, which is, as Collins himself acknowledges, only natural. Shakespeare wouldn't be Shakespeare if he didn't, finally, resist imitation.

I’ve just finished Warwick Collins’ new novel, The Sonnets, which draws its inspiration from Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence and the circumstances in which it was written. It’s a brave man who decides to narrate an episode from Shakespeare’s life in the first person - who opts, in other words, to impersonate the man himself - and an even braver one who pens a couple of extra sonnets at crucial moments in the narrative, but Collins pulls off the first with considerable elegance and skill, and the second by the skin of his teeth, which is, as Collins himself acknowledges, only natural. Shakespeare wouldn't be Shakespeare if he didn't, finally, resist imitation.The book weaves a context for some of the most famous sonnets, providing an entirely plausible sequence of events to explain the various mysteries surrounding their writing, although I admit to having a vested interest in Shakespeare’s presumed bisexuality, which gets short shrift here. What impressed me most about the book, though, wasn’t the way in which the sonnets are contextualized, psychologically adroit though this was, but the dramatic handling of Shakespeare’s relations with a bunch of finely-drawn characters, each with his or her role to play in the hothouse atmosphere of the poems' creation. Not only Southampton, whose initial foolhardiness and growing maturity are convincingly portrayed, but a host of other, minor and major, players.

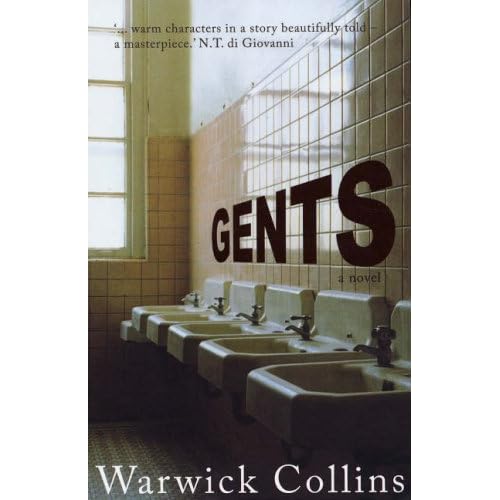

The parts of the book I enjoyed most, in fact, were the central chapters, a series of encounters in which Shakespeare is obliged, pretty much against his will, to take part in the world of political and dynastic intrigue surrounding his patron, a world of ever-increasing menace. If the sonnets are the framework around which the novel is constructed, its heart seems to me to be in these meetings, where Collins shows his extraordinary capacity to create both character and narrative tension through dialogue, something he demonstrated to great effect in his earlier novel, Gents. I particularly liked the scene with Southampton’s mother, but conversations with Lord Hunsdon and his mistress, and Master Florio and his wife, are just as effective, and chilling.

If I have one tiny qualm about the novel, it’s the wink towards the modern reader’s greater knowledge, as Shakespeare stumbles towards the familiar line, ‘If music be the food of love, play on…’ - if only on the grounds that the final version is the only one that scans properly. But that’s a very small quibble indeed with such a gripping and intelligent book.