Saturday, 23 February 2008

Charactus

Thursday, 21 February 2008

Five recommended portions a day

First copy

This is me, holding the first copy of Little Monsters to reach me. I'm thrilled, as you can see. Excitement always makes me look as though I've just been arrested and then told to smile. I still have the packaging in my hand. FedEx. The photogaph is very small because it's been cropped, and isn't intended to represent my innate modesty, which I no longer seem to have. I'm being introduced to people as a writer and I've stopped saying weelll and shaking my head in a self-deprecating way. I beam and offer to sign things. T-shirts. Skin.

This is me, holding the first copy of Little Monsters to reach me. I'm thrilled, as you can see. Excitement always makes me look as though I've just been arrested and then told to smile. I still have the packaging in my hand. FedEx. The photogaph is very small because it's been cropped, and isn't intended to represent my innate modesty, which I no longer seem to have. I'm being introduced to people as a writer and I've stopped saying weelll and shaking my head in a self-deprecating way. I beam and offer to sign things. T-shirts. Skin.Wednesday, 20 February 2008

Mother! Oh God, mother! Blood! Blood!

We had to help Scout with this one, which comes from a film whose opening scenes are set in this very city.

We had to help Scout with this one, which comes from a film whose opening scenes are set in this very city. Scout is a dog.

Tuesday, 19 February 2008

The poor dope. He always wanted a pool

Scout is working on a series of scenes from his favourite movies, using whatever prop comes to hand. This one is named after a place that isn't really that far from where we'll be in a week's time.

Scout is working on a series of scenes from his favourite movies, using whatever prop comes to hand. This one is named after a place that isn't really that far from where we'll be in a week's time.

Say it with African violets

This is what greeted us yesterday evening at what would have been 7 am in Italy. It was just after 10 pm. Any warmer? (And yes, it is.)

This is what greeted us yesterday evening at what would have been 7 am in Italy. It was just after 10 pm. Any warmer? (And yes, it is.)Thank you, Rachel.

Monday, 18 February 2008

Guess...

Friday, 15 February 2008

Veils

Cranach's Venus is too saucy for London Underground travellers, according to Transport for London, which has banned its use in an advertisement. This wonderful image, at once demure and enticing, had been chosen to advertise a Royal Academy show devoted to the great 16th century artist. It's one of a number of Venuses produced by Cranach: there's a particularly lascivious one, wearing a splendid hat and lounging against, if not actually dangling from, a tree while she listens to Cupid, who's no doubt used to this sort of behaviour. He's complaining that he's been stung by bees while trying to steal their honey. The painting represents the notion that all pleasure is mixed with pain, and it's an allegory that might be applied to Transport for London's decision to punish the RA for daring to bring a little artistic pleasure into travellers' lives.

Cranach's Venus is too saucy for London Underground travellers, according to Transport for London, which has banned its use in an advertisement. This wonderful image, at once demure and enticing, had been chosen to advertise a Royal Academy show devoted to the great 16th century artist. It's one of a number of Venuses produced by Cranach: there's a particularly lascivious one, wearing a splendid hat and lounging against, if not actually dangling from, a tree while she listens to Cupid, who's no doubt used to this sort of behaviour. He's complaining that he's been stung by bees while trying to steal their honey. The painting represents the notion that all pleasure is mixed with pain, and it's an allegory that might be applied to Transport for London's decision to punish the RA for daring to bring a little artistic pleasure into travellers' lives.Apparently the painting might 'offend'. A Transport for London spokesman said: "Millions of people travel on the London Underground each day and they have no choice but to view whatever ads are posted there. We have to take into account the full range of travellers and endeavour not to cause offence in the adverts we display." It's pretty clear to me that the only travellers of this 'full range' who might be offended by the painting are Muslim males and, at a pinch, our own home-grown fundamentalist killjoys. It's a pre-emptive strike in favour of bigotry, with the authorities trying to double-guess what might be 'upsetting' and who might be 'upset', though they can't actually say this.

Poor old Cranach. Poor us.

Thursday, 14 February 2008

Cream for (fat) cats

This smug bastard is called Sergio De Gregorio. He was elected senator two years ago for one of the smaller parties of Prodi's centre-left coalition. A few weeks after the election he had an epiphany, funded by Berlusconi, and discovered that he was actually centre-right. He defected for a rumoured €300,000, reducing the government's already tragically small majority to three. He then invented a party called Italiani nel Mondo (Italians in the World) and is no doubt collecting all the cash to which Italian political parties have an automatic right. His own personal newspaper for a start; after all he is a qualified journalist. You don't believe me? Visit his hilariously self-serving blog.

This smug bastard is called Sergio De Gregorio. He was elected senator two years ago for one of the smaller parties of Prodi's centre-left coalition. A few weeks after the election he had an epiphany, funded by Berlusconi, and discovered that he was actually centre-right. He defected for a rumoured €300,000, reducing the government's already tragically small majority to three. He then invented a party called Italiani nel Mondo (Italians in the World) and is no doubt collecting all the cash to which Italian political parties have an automatic right. His own personal newspaper for a start; after all he is a qualified journalist. You don't believe me? Visit his hilariously self-serving blog.The man isn't really worth bothering about but I was walking through the Testaccio quarter in Rome this morning and I saw fifty metres of wall covered with posters, possibly the first of this year's electoral campaign. It's not the most sophisticated advertising: a close up of the politician's porcine features with a slogan plastered across it. It was the slogan that made me stop and laugh out loud. It said Coraggio dei valori (The courage of values). I didn't have a camera with me, so I went to his blog to find the poster. And guess what? Typing coraggio dei valori into the search option I get: "Spiacente, stai cercando qualcosa che non c'è" (Sorry, what you're looking for isn't here).

Tuesday, 12 February 2008

Fright

And talking about women's rights, the Great Buffoon also pledged support to the suggestion of his tubby chum, opinionista Giuliano Ferrara, that an international moratorium be called on abortion, or 'murdering babies', as it's sometimes known. This has as much chance of passing as a moratorium on farting in private, but it's an easy way to say thank you forthe support he's already getting from the Vatican rag, Avvenire. And the latest news is that Ferrara, who has no children, is going to be running as a pro-life candidate. Well, here's photographic proof that he can do it. Run, that is.

Sunday, 10 February 2008

Sharia hits fan

Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, has created a brouhaha after suggesting on Radio 4 that the acceptance, or 'accommodation', in the UK of some aspects of Sharia law might be ‘unavoidable’. This is already the case, apparently, with Sharia courts in Britain dealing with thousands of cases involving marital or financial disputes, without a whiff of fundamentalist alarm. So Williams’ possibly slightly regretful recognition of the fact is a bland enough position to hold and wholly in line with the Anglican church’s take on the world as something you can’t do very much about, so why not rub along with it. Accommodation is all.

For the tabloids, though, his comments were tantamount to endorsing mutilation in public squares, mass infibulation and obligatory burkhas for all Page Three models. In their Talibanesque way, they want his head, his blood, and any other essential organs going, though what constitutes essential for an archbishop is material for theologians rather than lay thinkers. They accuse him of wanting to destroy Britain, a place they happily execrate, day in day out, for its appalling youth, corrupt government, filthy manners and fondness for employing Polish plumbers and paying them under the table.

Yet what on earth should someone like Williams say? Hang the infidels? Re-impose tithes? Make everyone sing Kumbaya with a cheesy smile, wearing Cliff Richard tee-shirts? He’s a major religious figure, after all, so it’s part of his remit to believe that state legislation should represent ethical choices. He’s also, by all accounts, an ecumenical type, so can hardly pretend that the only valid ethical choices are Anglican. Ergo, he’s shafted.

Perhaps all this fuss will persuade people that no religious belief of any kind should be allowed to interfere with the law, which represents and defends all members of a society regardless of their household gods, and which should have no truck with the kind of nonsense religious leaders - invariably old, invariably male, all too frequently celibate - spout with such punitive abandon.

If this is true for lapidation and the chopping off of hands, it’s equally true for the malicious interference of, for example, the catholic church in the business of countries like Spain and Italy. Let’s face facts. If you let one bossy old know-all into the legislating chamber, you open the door to the whole damn gang.

Friday, 8 February 2008

Returns

See you next week.

Wednesday, 6 February 2008

Home from home

It's the money, stupid

But the money has to be spent somehow. Let's see how: among the employees of Clemente Mastella, editor, is Clemente Mastella, journalist. Cost: €40,000 a year. Then there are travel expenses, because a newspaper needs to keep its finger on the local pulse. Annual cost (2005): €98,000. Most frequent beneficiaries: Sandra Lonardo Mastella (wife, and under investigation for collusion), followed by Elio and Pellegrino Mastella (sons). You can't fly everywhere, of course, so Pellegrino needs to fuel his Porsche Cayenne. He does it at the family's local petrol station. Cost (charged to Il Campanile): €2,000 every month. That's nothing compared to the money spent on public relations: €141,000 a year, plus €22,000 on gifts like chocolate and nougat from a small town in Clemente's home territory, Summonte, the birthplace of Mastella's sister-in-law and her husband, UDEUR deputy Pasquale Giuditta.

The main offices of Il Campanile are in Rome, in a rented building that used to belong to the state. Its new owners? Pellegrino and Elio Mastella.

At the last elections, UDEUR won 1.4% of the vote.

(My thanks to Susanna for passing this information onto me, and to Mauro Montanari of Corriere d'Italia/news ITALIA PRESS, who put it all together.)

Tuesday, 5 February 2008

Used already!

I wonder who could have flogged it. And for what? A cup of tea and a scone?

Sue Barker's beard

If, like me, you can't stomach Cliff Richard you'll enjoy this piece by Terence Blacker very much.

If, like me, you can't stomach Cliff Richard you'll enjoy this piece by Terence Blacker very much. My mother used to say: If you can't say anything nice, don't say anything at all. How wrong she was.

Monday, 4 February 2008

NQR

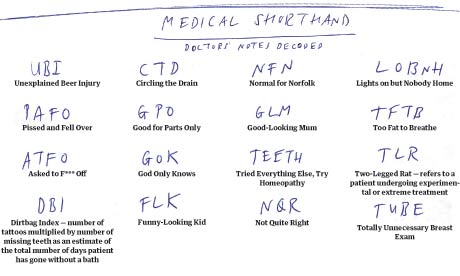

You may need to click on this to see it properly, but, believe me, it's worth it. It comes from a revealing article by Robert Hudson in today's Guardian, called Medical Confessions. I particularly like TEETH (Tried Everything Else, Try Homoeopathy).

You may need to click on this to see it properly, but, believe me, it's worth it. It comes from a revealing article by Robert Hudson in today's Guardian, called Medical Confessions. I particularly like TEETH (Tried Everything Else, Try Homoeopathy).It reminds me of the case notes that used to be kept at the Stoke on Trent Labour Exchange, where I spent six months of what would now be called a gap year signing people on, instead of being signed on myself. The interviewers didn't use acronyms, so it's lucky the notes never fell into the wrong hands (steer clear, Casetti!). Among the milder comments were 'smells like sick' and 'unfuckable, even with bag on head'. I remember being shocked and irresistibly drawn to the things, rectangles of cardboard with yellow paper and a ragged cover, held together by one of those elasticated ribbons with the metal tag. I didn't interview people myself, but I wonder if peer pressure would have worked its terrible way on me. Would I have been as cruel?

My job was to prepare the claim and collect the signatures every Thursday, standing at the desk all day as people queued. Those days it was cash; I'd give them a chit and they'd take it to the pay-out window. My worst client, though we didn't call them clients or, even more indefensibly, job-seekers, was a Mr Ignazio, possibly of distant Asian origin, rumoured to be a karate black belt and dangerously, unpredictably irascible. My colleagues used to hide his claim and watch me root through the metal tray for it, increasingly panicked, while Mr Ignazio stroked the cutting edge of his hand.

Saturday, 2 February 2008

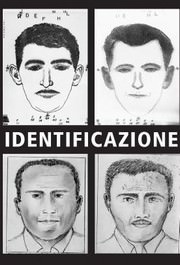

Mug shot

If you've spent more than a few days in Rome you'll probably have left the traffic of Largo Argentina behind you and paused by the turtle fountain in Piazza Mattei and thought, for a moment, how wonderful it must be to live there and wondered how that might be possible, and smiled to yourself. You might have taken out your drawing stuff and sketched the way the boys reach up to guide the turtles towards the water, the turtles already free of the guiding hand. After which, on your way to the heart of the Ghetto along Via della Reginella, assuming - as I do - that you're book-lovers, you'll have paused a few dozen yards away, outside a bookshop to see what its trestle table has to offer. Usually, it's a rum bunch of history books, fiction, a sprinkling of philosophy, mostly, but not entirely Italian. You may have decided to see what else the bookshop has to offer and wandered in. If you've bought anything, which is likely - because you can't resist - you'll have met the bookshop's owner, Giuseppe Casetti, a tallish, slim man with long off-white hair and a slightly guru-ish air about him.

If you've spent more than a few days in Rome you'll probably have left the traffic of Largo Argentina behind you and paused by the turtle fountain in Piazza Mattei and thought, for a moment, how wonderful it must be to live there and wondered how that might be possible, and smiled to yourself. You might have taken out your drawing stuff and sketched the way the boys reach up to guide the turtles towards the water, the turtles already free of the guiding hand. After which, on your way to the heart of the Ghetto along Via della Reginella, assuming - as I do - that you're book-lovers, you'll have paused a few dozen yards away, outside a bookshop to see what its trestle table has to offer. Usually, it's a rum bunch of history books, fiction, a sprinkling of philosophy, mostly, but not entirely Italian. You may have decided to see what else the bookshop has to offer and wandered in. If you've bought anything, which is likely - because you can't resist - you'll have met the bookshop's owner, Giuseppe Casetti, a tallish, slim man with long off-white hair and a slightly guru-ish air about him.Casetti's a character. He's been kicking around Rome for decades in one form or another, usually, though not only, as a bookseller. He's an anarchic sort of figure, linked to a series of artists, and movements, and events, and organisations. He was a friend of Frances Woodman, the American photographer, who killed herself when she was 23, when he called himself not Giuseppe, but Cristiano; he's half-poseur, half-benefactor, poised between

nostalgie de la boue and an eye for the main chance. He's dabbled in politics, and the art world, and made friends and enemies as people do. He's not as pure, or as radical, as he imagines himself to be - he's sentimental, for one thing, about the working class, and vain: I saw him at a Patti Smith concert some years ago in the Roman arena of Ostia Antica, swanning before the stage in a long white robe - but these are venial faults.

nostalgie de la boue and an eye for the main chance. He's dabbled in politics, and the art world, and made friends and enemies as people do. He's not as pure, or as radical, as he imagines himself to be - he's sentimental, for one thing, about the working class, and vain: I saw him at a Patti Smith concert some years ago in the Roman arena of Ostia Antica, swanning before the stage in a long white robe - but these are venial faults.And now he's in big trouble. Some years ago, he bought a bundle of moulding photographs from one of the people he buys stuff from; photographs that, apparently, had been thrown away by the police, dating back to the 50s and 60s. All kinds of stuff: mug shots, booty. He sat on them for years, finally deciding to organise a show in the space next to his bookshop, the ironically-named Museo del Louvre. He called on an old friend, Achille Bonito Oliva, to write the catalogue. Bonito Oliva, logorrheic as ever, obliged, citing Warhol and Nam June Paik. The show was set to hit the road two days ago. An article appeared in la Repubblica to pave the way.

It paved the way for someone from the Ministry of Fine Arts and, hot on his heels, the police. The photographs have been seized, along with Casetti's computer and papers of all kinds. His entire stock has been confiscated, the shelves stripped, searches conducted behind them, as though the bookshop were owned by Al Qaida. Casetti is being treated like a criminal, interrogated, demeaned. I imagine that at some point they'll be taking his photograph, full face and profile. He's become the unwilling centre of his own show.

Casetti's not worth the effort the police appear to be putting into this case. It's as though some nerve has been touched. Official carelessness perhaps. Casetti's past as a flip-flopping fellow-traveller of the left. Culture, the great pretender, to which one responds with a gun. Bonito Oliva, convinced of the centrality of art and of his own centrality within it, sniffs a rat. He's going to be 'writing something about it.' In the meantime, a bookseller who has done nobody any serious harm, whose endeavour to keep alive an ember of modernism in a resolutely post-modern world is touchingly heroic, finds himself in a bookshop without a book.

Ross Leckie: Hannibal

One of the problems with historical fiction is that the reader is likely to have a fairly clear idea of what happens. This is particularly the case when the fiction deals with the illustrious dead. Novels about Napoleon and Marie Antoinette and Henry VIII may have a lot of incidental stuff to tell us, but the essential tension of fiction – will he die in exile? will she live? will he get married? – is necessarily absent.

One of the problems with historical fiction is that the reader is likely to have a fairly clear idea of what happens. This is particularly the case when the fiction deals with the illustrious dead. Novels about Napoleon and Marie Antoinette and Henry VIII may have a lot of incidental stuff to tell us, but the essential tension of fiction – will he die in exile? will she live? will he get married? – is necessarily absent.There are ways around this, of course. The writer can take a leaf from Robert Graves’ Claudius novels, choosing a relatively minor figure and dividing the life into two. Alternatively, the book can portray the famous, about whom pretty much all is known, through the eyes of the real protagonists, as Mary Renault does in her wonderful novels about the adult Alexander and the Athens of Socrates and Plato. Other less scrupulous historical novelists have simply invented love affairs, illegitimate children, mysterious deaths, in an effort to sex the whole thing up.

Ross Leckie, in Hannibal (Canongate, UK, 2008), has chosen a more difficult option. There can be few readers who don’t already know that Hannibal tried to conquer Rome by leading his army, complete with elephants, across the Alps in winter, and that he failed. And, really, that’s all there is to it. So it’s a pleasure to be able to say that Leckie, with great skill, has taken this basic story – the Carthaginian leader’s campaign against the Roman empire – and created a novel that works not only as a picture of an unutterably foreign world and time but also as a page-turner.

The world the novel portrays, vividly and with impressive detail, is Hannibal’s, from his childhood to his death. Hannibal’s world is war, and the violence of the novel, gruesome, unrelenting and explicit, is rooted in the logic of war. From the opening scene, in which a Roman envoy loses his nose and tongue, to the almost off-hand way in which Hannibal slaughters more than 4,000 of his own men for their own good; “Without me, they would have been crucified by the Romans”, the novel never loses its power to shock.

But what transforms the book from a mere account of a bloody and doomed campaign, however adroitly written, into something more solemn and more terrible is Hannibal’s gradual awareness, as he loses his child, his wife, his closest friend, his army, that he doesn’t know what he’s fighting for. More to the point, he doesn’t know what war itself is for. His driving force, finally, is hatred, of Rome and, later, of Carthage, and the measure of the man is that he knows this is not enough.

At a memorable moment early in the novel, Hannibal has the chance to choose between gory revenge and mercy; between the world of Carthage and another, more human world represented by Silenus, his Greek tutor. He chooses Carthage. What makes the moment significant is that he knows the weight of his choice and the extent to which he is diminished by it. It’s to Leckie’s credit that Hannibal, despite the final futility and wastefulness of his life’s work - a futility of which he is all too aware himself - emerges from this novel as a figure of stoical, appalling grandeur.

One small complaint, addressed not to Leckie but to his publisher. Surely a novel that deals with an epic journey from Carthage, via Spain and southern France, across the Alps, to the toe of Italy could have been supplied with a map?